Privatisation and Education for Disadvantaged Groups in India: institutional responses and social implications

Funded by a grant from the Privatisation in Education Research Initiative (PERI) launched by the Open Society Institute

Grant Value: USD 25,000

Partners: CORD

Grant Value: USD 25,000

Partners: CORD

policy & research contextIndia's landmark Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009 (RTE Act), effective as of April 2010, is the result of a long process of deliberation and public debate, It is the first official Central Government legislation to fully confer the right to education by law and extend it across the country. This marks a significant shift in the formal policy and legal frameworks governing education in India.

Nonetheless, controversy surrounds the Act and its provisions in a number of areas, the most prominent being Section 12(1)(c) compelling all private schools to allocate 25% of their places in Class 1 (or pre-pre-primary as applicable) for free to socially and economically disadvantaged children, to be retained until they complete elementary education (Class 8). Proponents claim that this is necessary for the state to achieve universal elementary education because of insufficient state sector capacity; critics maintain that the provision marks the most explicit institutional legitimization of the private sector without sufficient effort to strengthen the decaying state sector. Complicating the implementation of the RTE Act are powerful private school lobbies that launched a Supreme Court case arguing that the provision impinged on their right to run their schools without undue government interference, and that the Act was unconstitutional. |

research aims & questionsThe main aim of the study was to shed light on the early phase of implementation of the RTE Act, with special reference to the private sector. The study sought to understand the way in which the RTE Act directed local policy action, the way it was mediated/implemented by local schools, and the experiences of disadvantaged households accessing schooling in the context of the RTE Act, with particular attention on how they accessed private schools and their attempts in securing places under the 25% free seats provision.

Research Questions

|

research methodsDelhi was chosen as the location for the study as it is the political centre of the country and one of the first sites to implement the Act. One urban slum was selected as the field site. The field site had a concentration of disadvantaged families and there was a mix of government and private schools.

Fieldwork was conducted between June 2011 and January 2012, with the bulk of the household and school data collected between June and September 2011 and documentary analysis completed in April 2012. Data were collected through the following methods: a household survey of 290 households in one resettlement block and adjacent squatter colony in the selected slum; semi-structured interviews with 40 households drawn from this larger sample; semi-structured interviews with the seven most accessed local government and private schools; semi-structured interviews with policy officials and implementers; and documentary analysis of the RTE Act and rules at the level of the Central and Delhi Governments, relevant preceding bills and associated documents, and government notices and circulars. |

...we were just settled on a piece of vacant land, in 25-yard plots. A brick was put in each corner and we were told ‘Brother, this is your portion’. People put up shacks and lived in them for years. Pakka houses were built only after two to four years. |

key findingsLocal and School Implementation

RTE implementation was affected by a number of factors including: -perceived lack of clarity on concrete policy directives -lack of appropriate institutional structures -need for bureaucrats, officials, and schools to reconceptualise education for all as a right rather than the typical view as an area of special programme delivery -lack of a clear and timely grievance redressal mechanism -above all, the social embeddedness of schools and education in deep and hierarchical power relations School Responses to the Act All school respondents claimed to be well aware of the Act but there were significant variations across schools in implementing the provisions, and in some cases, non-compliance. Responses thus indicated a considerable gap between the official articulation of the Act’s provisions and what was intended in principle, and its implementation in practice. Two private school mediation strategies regarding the free seats provision were evident. The first was misinterpretation (which may or may not be deliberate), and the second was evasion. Household Experiences of Accessing Schooling and Free Private School Places Data expose that fee-free freeship private education in elite schools for survey households was not a reality. Data showed substantial related costs for households accessing these schools under the quota. The cheapest option was still government schooling, and was accessed by the majority of the poor and very poor households in our sample. The next cheapest were local lower-fee schools even if paying fees. Freeship children came from relatively more economically stable families and had parents that were relatively better schooled. These parents showed tremendous persistence, approached a number of schools, and made contacts with the ‘right’ people (e.g. local politicians, friends and family ‘in the know’, local NGOs). It was evident that households, including those that successfully secured freeships, were not (made) aware of the full extent of the provision, and all paid significant costs to access freeship schools. In addition to cost barriers, the opacity of the freeship application process, timeliness of freeship announcements to applicants, social networks, and household ease and familiarity with interacting with private schools (more desirable higher-fee private schools in particular), posed significant barriers in households’ attempts at securing a free place. Furthermore, household and school-level data showed that schools mediated the way that the free seats provision and other RTE provisions were instituted, resulting in information asymmetry for households on their entitlements. |

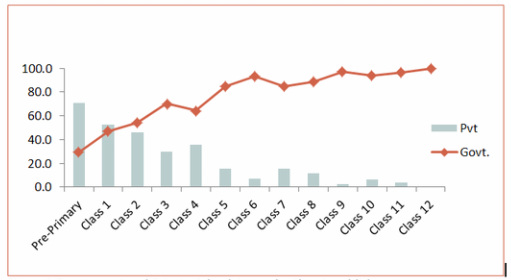

Snippets from the dataI think with the RTE there is a shift in paradigm. It is now a rights-based thing. It is no more a delivery that you are doing out [of] charity or philanthropy. It’s not a programme-based service. So this shift many people have not understood. [...] That’s the biggest problem. Because ideologically if you don’t understand, ‘That now this whole service has become a right,’ you sort of don’t take it that way. [...] the approach now is this that it’s a right now. They bloody will do it now. You’re not doing charity or anything. You absolutely have to do it. Now it’s become a right. --Interview with RTE implementer Of course, I think that the EWS quota is important. The stipulation is to give free education to 25% of your students [...] It has to be 25% of the total number enrolled. If four children are admitted, one has to be in the EWS category. One seat out of the four has to be kept vacant. As grade levels increase, private school access decreases and government access increases.

|

research output

Publications and Conference Papers

Srivastava, P., & Noronha, C., The myth of free and barrier-free access: India's Right to Education Act--private schooling costs and household experiences. Oxford Review of Education, 42(5), pp. 561-578, 2016. Access it here.

Srivastava, P., & Noronha, C., Institutional framing of the Right to Education Act: contestation, controversy, and concessions. Economic and Political Weekly, 49(18), pp. 51-58, 2014. Download here.

Srivastava, P., & Noronha, C., 'Early private school responses to India's Right to Education Act: implications for equity', in I. Macpherson, S. Robertson, & G. Walford (Eds.), Education, Privatisation and Social Justice: case studies from Africa, South Asia and South East Asia, Oxford, Symposium Books, 2014. Click here for abstract and scroll down.

Noronha, C., & Srivastava, P., 'India's Right to Education Act: household experiences and private school responses.' Education Support Program Working Paper Series 2013, No. 53. PERI, Open Societies Foundations, 2013, pp. 52. Download here.

Noronha, C., & Srivastava, P., The Right to Education Act in India: focuses on early implementation issues and the private sector. Report submitted to the Privatisation in Education Research Initiative, Soros Open Society Institute, Ottawa/New Delhi, University of Ottawa/CORD, 2012, pp. 159. Click here for abstract and scroll down.

Srivastava, P., 'Beyond ‘privatisation’: new conceptualisations and macro-policy framing taking India’s Right to Education Act as a case.' 12th UKFIET Conference 2013, Oxford, 10-12 September 2013.

Srivastava, P. ‘Institutional framing of the Right to Education Act: contest, controversy, and concession.’ XV Comparative Education World Congress, Buenos Aires, 24-28 June 2013.

Noronha, C., & Srivastava, P. 'Private schooling and possibilities of change post-RTE? Findings from a study in a slum community in Delhi.' Right to Education Act Dissemination Workshop, New Delhi, 25 September 2012.

Noronha, C., & Srivastava, P., ‘The Right to Education Act in India and private schooling: a case study in Delhi.’ Paper presented at the PERI Asia Regional Conference, Open Society Institute, Kathmandu, Nepal, 26-28 September 2012.

Srivastava, P., ‘The implementation of the 2009 Right to Education Act in India: private schools and access.’ 56th Annual Conference of the Comparative International Education Society, San Juan, Puerto Rico, 22-27 April 2012.

Srivastava, P., & Noronha, C., ‘Privatisation and education for disadvantaged groups in India: institutional responses and social implications.’ Paper presented at the PERI Asia Regional Conference, Open Society Institute, Kathmandu, 18-20 August 2011.

Research and Dissemination Workshop

Early Years of Implementing RTE 2009: issues and challenges, New Delhi, 25 September 2012

Click here for more information

Srivastava, P., & Noronha, C., The myth of free and barrier-free access: India's Right to Education Act--private schooling costs and household experiences. Oxford Review of Education, 42(5), pp. 561-578, 2016. Access it here.

Srivastava, P., & Noronha, C., Institutional framing of the Right to Education Act: contestation, controversy, and concessions. Economic and Political Weekly, 49(18), pp. 51-58, 2014. Download here.

Srivastava, P., & Noronha, C., 'Early private school responses to India's Right to Education Act: implications for equity', in I. Macpherson, S. Robertson, & G. Walford (Eds.), Education, Privatisation and Social Justice: case studies from Africa, South Asia and South East Asia, Oxford, Symposium Books, 2014. Click here for abstract and scroll down.

Noronha, C., & Srivastava, P., 'India's Right to Education Act: household experiences and private school responses.' Education Support Program Working Paper Series 2013, No. 53. PERI, Open Societies Foundations, 2013, pp. 52. Download here.

Noronha, C., & Srivastava, P., The Right to Education Act in India: focuses on early implementation issues and the private sector. Report submitted to the Privatisation in Education Research Initiative, Soros Open Society Institute, Ottawa/New Delhi, University of Ottawa/CORD, 2012, pp. 159. Click here for abstract and scroll down.

Srivastava, P., 'Beyond ‘privatisation’: new conceptualisations and macro-policy framing taking India’s Right to Education Act as a case.' 12th UKFIET Conference 2013, Oxford, 10-12 September 2013.

Srivastava, P. ‘Institutional framing of the Right to Education Act: contest, controversy, and concession.’ XV Comparative Education World Congress, Buenos Aires, 24-28 June 2013.

Noronha, C., & Srivastava, P. 'Private schooling and possibilities of change post-RTE? Findings from a study in a slum community in Delhi.' Right to Education Act Dissemination Workshop, New Delhi, 25 September 2012.

Noronha, C., & Srivastava, P., ‘The Right to Education Act in India and private schooling: a case study in Delhi.’ Paper presented at the PERI Asia Regional Conference, Open Society Institute, Kathmandu, Nepal, 26-28 September 2012.

Srivastava, P., ‘The implementation of the 2009 Right to Education Act in India: private schools and access.’ 56th Annual Conference of the Comparative International Education Society, San Juan, Puerto Rico, 22-27 April 2012.

Srivastava, P., & Noronha, C., ‘Privatisation and education for disadvantaged groups in India: institutional responses and social implications.’ Paper presented at the PERI Asia Regional Conference, Open Society Institute, Kathmandu, 18-20 August 2011.

Research and Dissemination Workshop

Early Years of Implementing RTE 2009: issues and challenges, New Delhi, 25 September 2012

Click here for more information